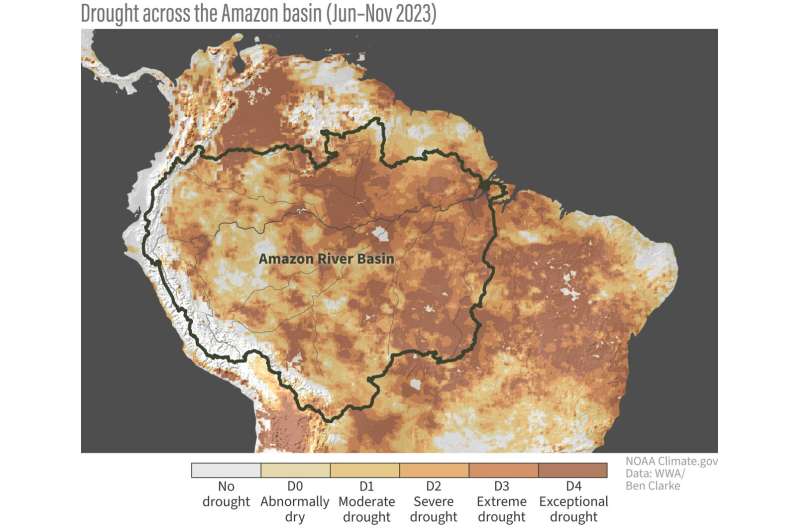

The devastating drought in the Amazon River Basin that reported in October has continued into Northern Hemisphere winter, which is the heart of the wet season in the southern part of the basin. The drought is cutting off rural and riverside communities from food supplies, markets for their crops, and health services; causing electricity blackouts due to hydropower disruptions; and forcing water rationing in some urban areas.

Droughts are common in the Amazon during El Niño. The details vary from one El Niño to the next, but the Amazon is generally one of the rainfall losers, and the current El Niño is a strong one. In 2023, however, the rainfall shortages also came with extreme heat, which intensifies evaporation and drying of the soil.

Based on preliminary analysis of observations and computer model simulations, a team of experts with the World Weather Attribution project has concluded that human-caused global warming played a significantly larger role than El Niño in intensifying the 2023 Amazon drought.

Compared to a world where global warming didn’t happen, models estimate that today’s warmer world doubled the precipitation deficits (“meteorological drought”) that could have been expected from El Niño alone, but even that impact was small compared the way rising temperatures amplified water stress (“agricultural drought”).

The drought would have been “severe” without global warming, but the long-term rise in temperatures intensified it by two categories, turning the 2023 drought into an “exceptional” one that has become the worst on record.

When the scientists took into account the combined impact of rainfall shortages and heat-driven evaporation of soil moisture (“agricultural drought”), they concluded that the return interval for the 2023 drought in today’s climate was closer to a 1-in-50-year event on average (meaning a 2% chance of happening each year). Such a drought was 30 times less frequent in the simulations of the world without global warming.

The increases in drought frequency and intensity reported by the World Weather Attribution team are based on observed global warming to date, about 1.2°C (2.2°F) above the pre-industrial average. When global warming reaches 2°C (3.6°F), models project that agricultural droughts as intense as the 2023 event will increase in frequency by a further factor of 4, giving them an average return interval of 10–15 years.

Such a dramatic increase in the return interval of exceptional droughts would push the Amazon Rainforest ever closer to what some ecologists think may be an Amazon “tipping point,” beyond which the Amazon will become like a savanna.

At least half of the rain that falls over the Amazon basin is recycled moisture that the trees themselves inhale from the soil and breathe back into the atmosphere. As deforestation and fire degrade the forest along edges and roads, the Amazon’s rain-making capacity gets weaker.

Dry seasons get longer, and surface water dwindles. Mature trees succumb to droughts, and new ones fail to replace them. These changes are already occurring at a local scale in the southern and eastern parts of the Amazon River Basin. Past a certain point, models project that the large swaths of tropical rainforest will rapidly flip into a savanna-like landscape.

Where is that tipping point? In a 2018 essay in Science Advances, two Amazon experts pointed out that many models project that without deforestation and fires, an Amazon tipping point wouldn’t be reached until global warming surpassed 4°C. Without climate change, models estimated it would take deforestation rates of about 40% to push the Amazon past its tipping point.

Individually, those thresholds may be far off. But the combined “negative synergies” of multiple human impacts—fire, deforestation, and climate change—are very likely to lower the threshold. In short, the authors argued in a follow-up essay in 2019, the tipping point may be a lot closer than we think.