Wind project costs in Europe have risen by 30-35% since before the pandemic, according to one senior banker who works in renewables. The profitability of new projects in Spain, measured by their internal rate of return, plunged from a peak of 14% in late 2022 to a trough of 6% in mid-2023, according to UBS. Acciona Energía’s shares are down 43% since the start of last year.

All those challenges make repowering more difficult. So too do permitting regulations and the management of electricity grid connections, which the wind sector complains are still insensitive, if not hostile, to its needs.

To make matters worse, wind developers are facing their own version of the “greenlash” against the costs of decarbonisation. The idea that “wind is woke” has taken hold among some critics who view renewables as a partisan leftwing cause.

More critically, the wind industry endured a torrid 2023, getting battered by a combination of higher interest rates, elevated commodity prices, uncertain demand and strained supply chains. Siemens Energy, whose wind unit makes turbines, needed a €15bn bailout last year. Danish group Ørsted, the world’s largest offshore wind developer, this month announced up to 800 job cuts and slashed targets for new projects having booked $4bn of impairments last year.

The battle against a warming planet may be critically urgent, but because wind power infrastructure is ageing, a crucial part of Europe’s energy future is a question rooted in the past: what to do with its oldest turbines?

Giles Dickson, chief executive of WindEurope, says: “Of all of your old wind farms, what percentage are getting repowered? The answer is not enough. It’s quite a small proportion.”

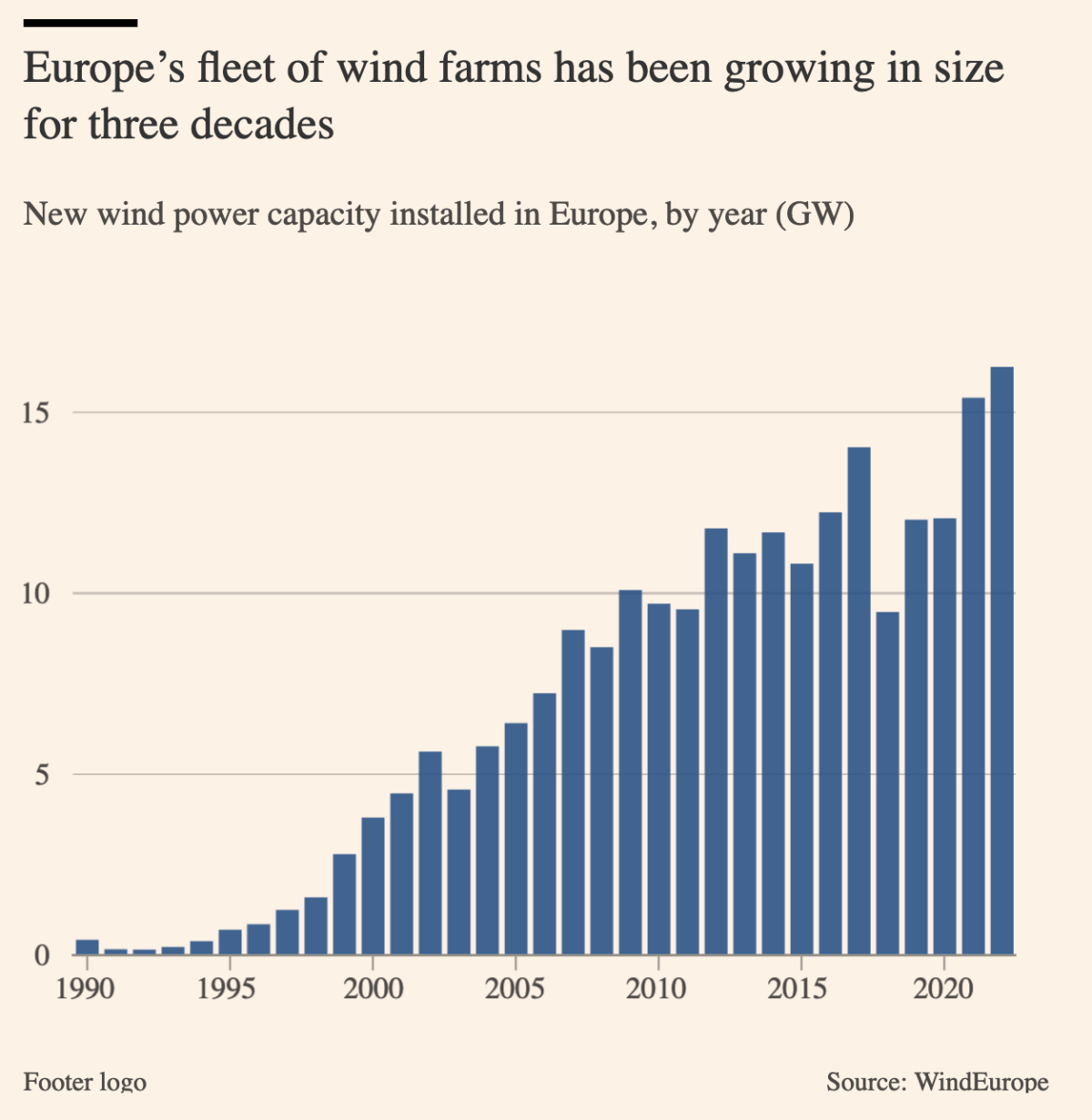

About a fifth of the continent’s roughly 90,000 onshore turbines are at least 15 years old — and the normal lifespan of a wind farm with minimal maintenance is 20 years. In Spain, a pioneer of wind power in the 1990s along with Germany and Denmark, wind parks aged 15 or older are half of the total — the highest proportion in the EU, according to trade body WindEurope.

The end-of-life choices made by turbine owners, who must weigh up whether to invest more or walk away, have broader consequences. Their decisions will help determine how much progress the EU makes towards its goal of fostering energy independence and reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Spain should be moving in the opposite direction. Its total wind capacity today is 30GW and its climate plan envisages more than doubling that to 62GW over the next six years. By 2030, renewables are meant to account for 81% of the country’s electricity generation.

That is why Madrid, and the EU, are pushing for what experts call repowering: taking down the oldest turbines and using the same sites to erect cutting-edge new windmills, which are taller, more efficient and pump out more electricity. But the shift can be a costly, complicated process.

A typical 20-year-old machine, whose blade tips reach as high as 90 metres, generates 800kW. A new model produces 7,000kW with blades that rise to 240m or more. A single rotation produces more energy than an average Spanish household consumes in a day.

Since the early days of wind power, new turbines have sparked not-in-my-backyard resistance from local residents worried about alien objects ruining their rural vistas, as well as noise, electromagnetic interference and the “shadow flicker” cast by moving blades.

The industry finds solace in surveys that suggest people living close to existing wind farms are more tolerant of them than those with no experience. First-hand contact tends to allay the worst fears, or at least demonstrate that the projects bring in new money: developers stump up local taxes, pay landowners to lease turbine plots and offer “sweeteners” to local communities by renovating village halls or building sports centres.

Legal challenges rooted in environmentalism, however, are frequent. In Galicia in north-west Spain, roughly 100 projects have been stalled by disputes lodged with the region’s top court, says the local wind trade body. In 2022, the same court annulled the authorisation for the repowering of a wind farm where the owner, Portugal’s EDP, had already replaced 61 turbines with 7 larger ones. But Spain’s Supreme Court overturned the decision this month.

The key players in many legal battles are birds. The taller turbines become, the greater the collision threat they pose. Their blades may appear to move slowly, but the tips can be flying at nearly 300km an hour, says José Antonio Sarrión, an ornithologist, or bird expert, who has worked for wind developers in Tarifa. “When a blade hits a vulture, the bird is often split in half,” he adds.

Acciona Energía recorded 800 bird and bat deaths at its 168 Spanish wind farms in 2023, including 10 endangered creatures. Ten is “a meaningful number,” says Entrecanales. “But it’s not huge.”