The ocean floor is shaping up to be the world’s next theater of global resource competition — and China is set to dominate it. The sea is believed to hold several times what land does of these rare metals, which are critical for almost all of today’s electronics, clean-energy products and advanced computer chips. As countries race to cut greenhouse gas emissions, demand for these minerals is expected to skyrocket.

When deep-sea mining begins, China — which already controls 95 percent of the world’s supply of rare-earth metals and produces three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries — will extend its chokehold over emerging industries like clean energy. Mining will also give Beijing a potent new tool in its escalating rivalry with the United States. As a sign of how these resources could be weaponized, China in August started restricting exports of two metals that are key to U.S. defense systems.

In the case of polymetallic nodules, that means sending robotic vehicles as deep as 18,000 feet to the vast, dark seafloor, where they will slowly vacuum up about four inches of seabed, then pump it up to a ship.

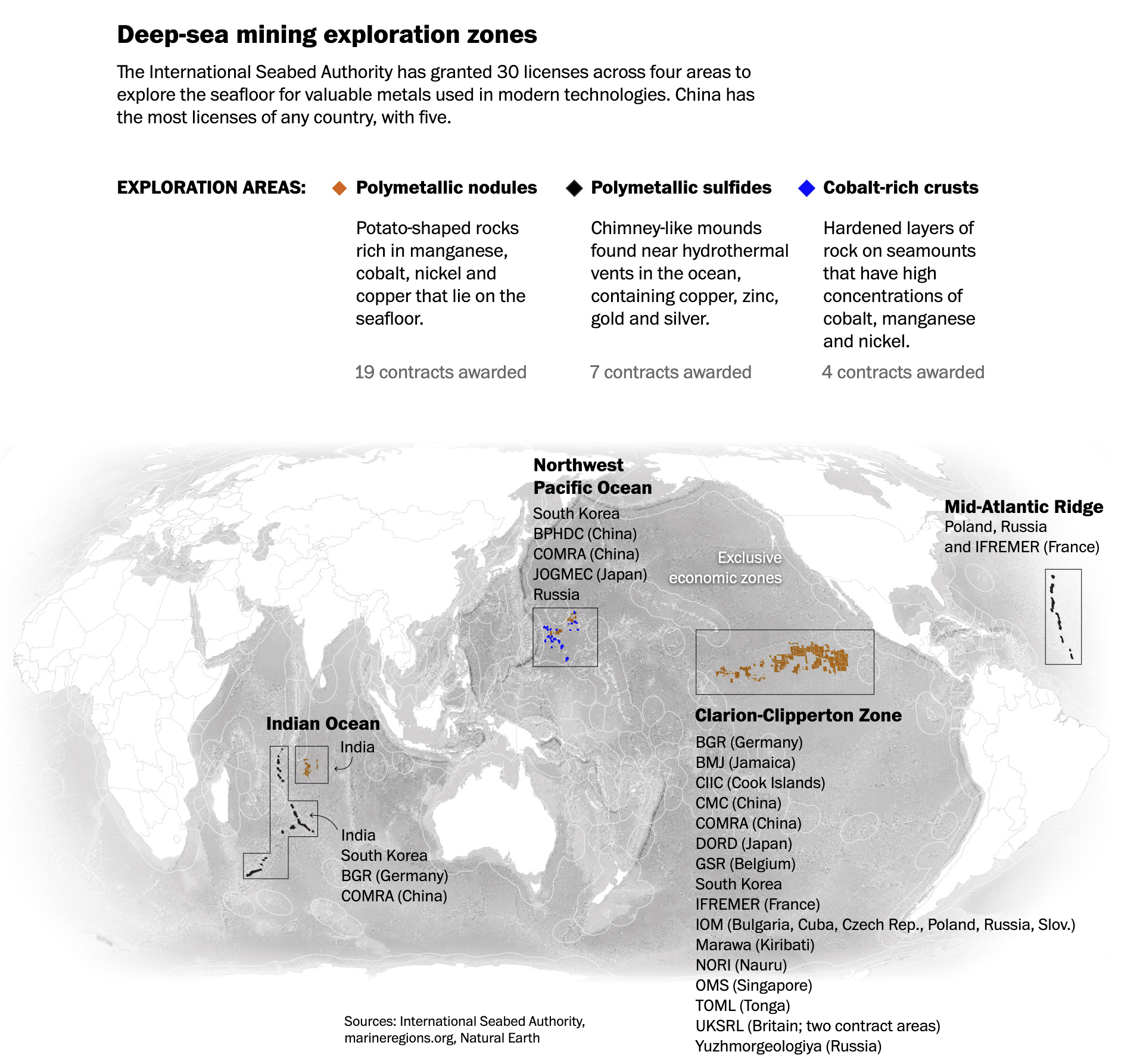

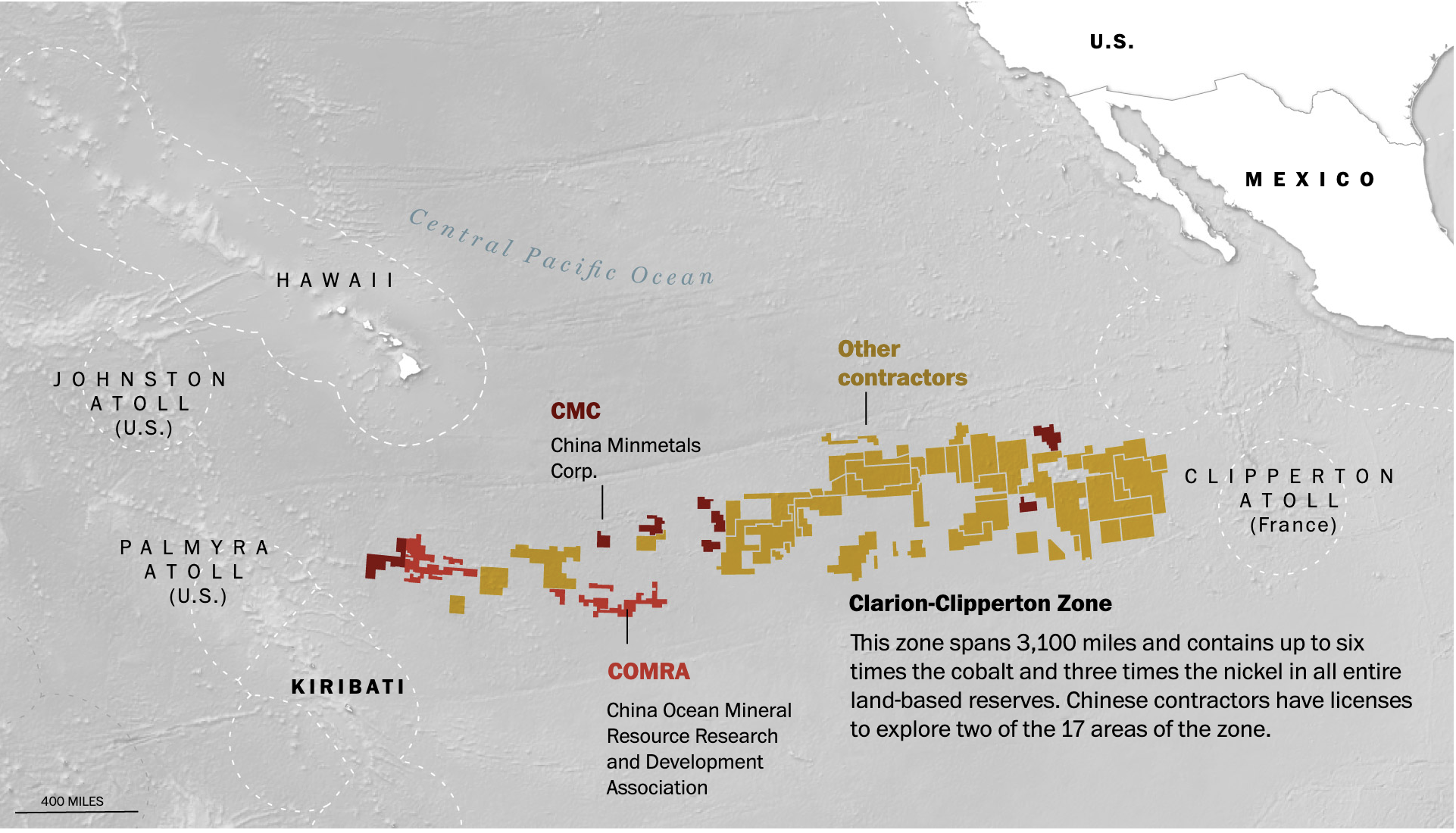

The area marked for mining, though less than 1 percent of the total international seabed, would still be huge. The 30 exploration contracts cover 540,000 square miles but are concentrated in an expanse of the Pacific called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Spanning 3,100 miles, it is wider than the contiguous United States and contains up to six times the cobalt and three times the nickel in all land-based reserves.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is under pressure to come up with rules after the Pacific island of Nauru, partnering with Canadian firm The Metals Company, in 2021 triggered a provision that requires the organization to allow mining within two years, even if a regulatory code is not in place.

ISA member countries must come to an agreement on a final code or face the possibility of mining proceeding unrestricted. For now, further discussion of the “two-year rule” has been shunted to next year.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as researchers realized the extent of the ocean’s mineral wealth, the question over who has a right to those resources became ideological.

Rich countries like the United States wanted to operate on a first-come, first-served basis while China, a developing country, sided with Global South nations and said the spoils should be shared. China’s side won, and the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), agreed upon in 1982, has been ratified by most countries. The United States recognizes the convention but has not ratified it, in part because of opposition to its provisions on seabed mining.

Under the convention, the ISA was established in 1994 and charged with overseeing deep-sea mining. U.S. critics say acceding to the treaty would undermine U.S. sovereignty on the high seas by handing power to the ISA.

At the heart of the debate about deep-sea mining is whether this can be done in a way that doesn’t harm ocean ecosystems and species. Scientists say this kind of activity on the seafloor will destroy a library of information important to medical breakthroughs, understanding the origins of life, and other advances.

In addition to polymetallic nodules, two other types of deposits are being considered for ocean mining — polymetallic sulfides, found in hydrothermal vents, and metal-rich cobalt crusts, which lie in hardened layers along underwater mountains. Both will be even harder to mine.

Environmentalists also worry that China’s history of privileging industry over the environment will lead to diluted regulations. Residents and authorities in southeastern China are still grappling with the widespread soil and water pollution caused by a boom in mining for rare-earth metals starting in the 1990s.