There’s enough water frozen in Greenland and Antarctic glaciers that if they melted, global seas would rise by many feet. What will happen to these glaciers over the coming decades is the biggest unknown in the future of rising seas, partly because glacier fracture physics is not yet fully understood.

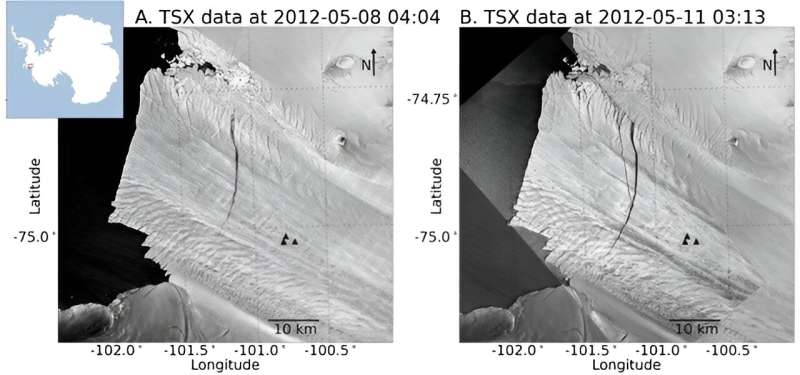

A critical question is how warmer oceans might cause glaciers to break apart more quickly. University of Washington researchers have demonstrated the fastest-known large-scale breakage along an Antarctic ice shelf. Their study, recently published in AGU Advances, shows that a 6.5-mile (10.5 kilometer) crack formed in 2012 on Pine Island Glacier—a retreating ice shelf that holds back the larger West Antarctic ice sheet—in about five and a half minutes. That means the rift opened at about 115 feet (35 meters) per second, or about 80 miles per hour (129 kilometres per hour).

A rift is a crack that passes all the way through the roughly 1,000 feet (300 meters) of floating ice for a typical Antarctic ice shelf. These cracks are the precursor to ice shelf calving, in which large chunks of ice break off a glacier and fall into the sea. Such events happen often at Pine Island Glacier—the iceberg observed in the study has long since separated from the continent.

In other parts of Antarctica, rifts often develop over months or years. But it can happen more quickly in a fast-evolving landscape like Pine Island Glacier, where researchers believe the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has already passed a tipping point on its collapse into the ocean.