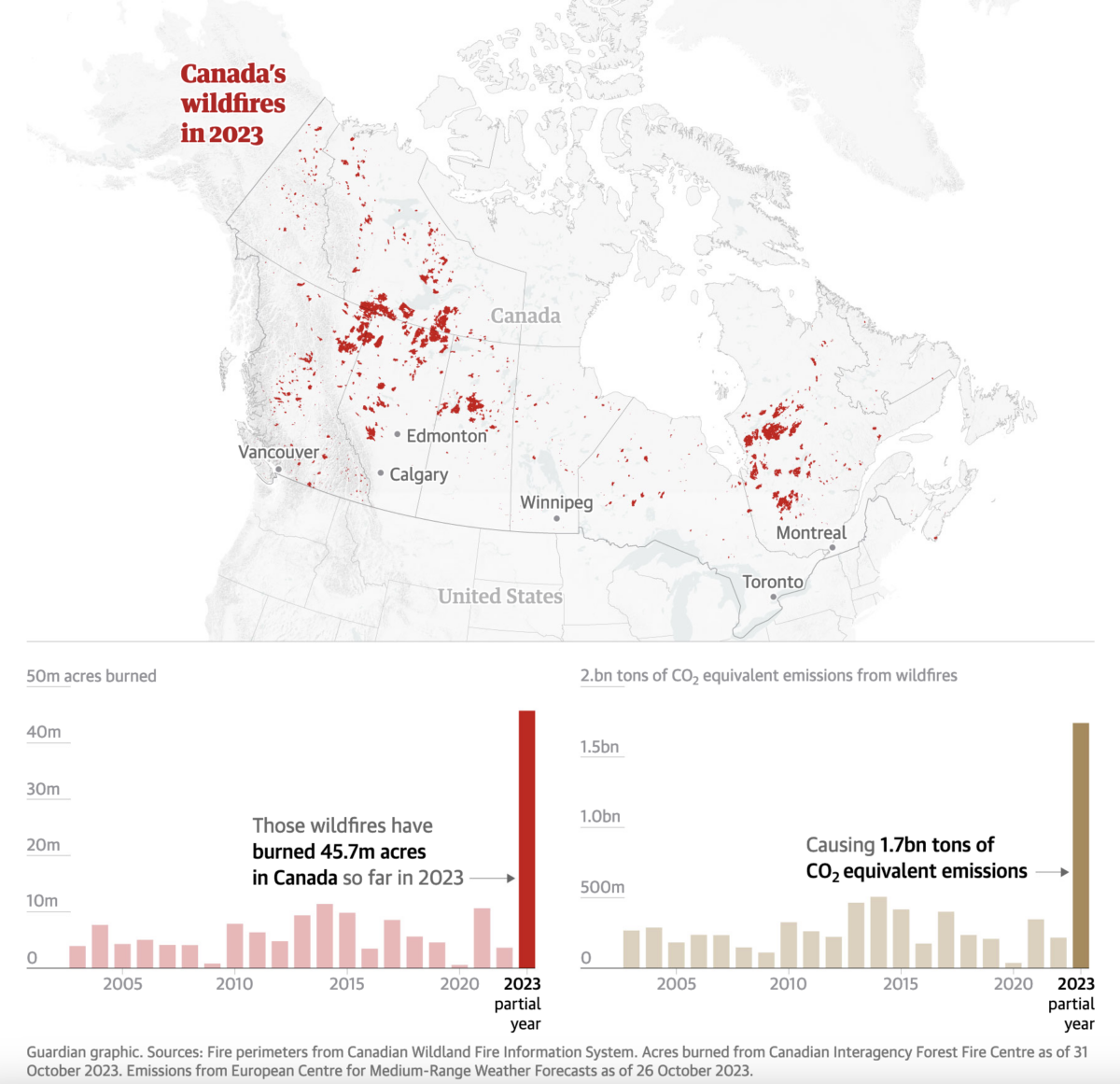

Fire ravaged Canada in 2023 like no other year, by a stupendous margin. A record 45.7m acres (18.5m hectares) went up in flames, an area about twice the size of Portugal, shattering the previous annual record nearly three times over. From the spring onwards, more than 6,500 fires sprang up, unusually, across the whole country, tearing through Nova Scotia in the east to British Columbia in the west.

The fires were largely centered on Canada’s vast boreal forests, a trove of habitat for creatures such as moose, bears and songbirds and a crucial carbon bank that blankets an area larger than India, representing about a quarter of the world’s remaining intact forest.

“It has been an exceptional, epic year,” said Stephen Pyne, a fire historian at Arizona State University. “We are watching mythology become ecology – it’s a slow-motion Ragnarök. We’ve had ice ages in the past but we are now living through what I call the ‘pyrocene’. Imagine an ice age but instead of ice as a forming feature, we have fire.

The sheer intensity of some of these blazes means it is not clear whether the dominant fir and spruce trees in the boreal forest will come back as before – it may be a different, more flammable mixture of vegetation that regrows in their place.

“We are seeing an environment adapted to ice being driven off to be replaced by one that is adapted to fire,” said Pyne. “If you have these sort of fires, these sort of monsters, you start to see quite big changes.”

According to data from the European Union’s satellite monitoring service, more than 1.7bn tons of planet-heating gases have been released this year by the enormous fires – about three times the total emissions that Canada, a major fossil fuel-producing nation, itself produces each year.

Such huge emissions, eclipsing in a single year any measure, however ambitious, to cut pollution from cars or factories by a country like Canada, are a major drag upon efforts to stem the climate crisis. The majestic boreal forests, much like the Amazon rainforest that now emits as much carbon as it sucks up and is tipping towards becoming a savannah, suddenly appear to be a danger to the world’s climate rather than a key safeguard.

“The forest isn’t our friend any more,” he added. “This was supposed to be a natural reservoir, our carbon bank, but now the bank isn’t stable. There’s a bank run. It is going to burn, as well as the peat below the ground that is also a huge store of carbon. It’s potentially a carbon timebomb.”

For Canada, the challenge of maintaining its huge forests in an age of rapid climate breakdown looms large. The country has about 10% of the world’s forests and a third of this land has burned in the past 40 years. Even as temperatures plummet and snow starts to arrive over winter, many of the outbreaks will continue to smolder underground as “zombie” fires, possibly then rearing up again next year.