A world where global mean surface temperature has increased 3°C will be characterized by widespread and intense heat stress, extreme weather events, ruptured and unproductive marine and terrestrial ecosystems, broken food systems, disease and morbidity, intense decadal megadrought, freshwater scarcity, catastrophic sea level rise, and large numbers of migrant populations. By 2050, under these malignant conditions, up to 1.2 billion humans could be displaced by climate change.

Climate change and global sustainability

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere and the climate crisis is now well underway. Global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions set a new record in 2023, rising an estimated 1.1%, the third annual increase in a row since the COVID-19 recession. With a record 1.45°C of anthropogenic global heating reached in 2023, we already see nearly one-third of the world population exposed to deadly heat waves, a 9-fold increase in large North American wildfires, record-setting regional-scale megadrought, the Antarctic ice sheet losing nearly 75% more ice between 2011 and 2020 than it did for the period 2001 and 2010, animal and plant extinctions projected to increase 2- to 5-fold in coming decades.

Scientists suspect the last several years have been warmer than any point in more than 125,000 years. Yet demand for oil climbed to over 100 million barrels per day in 2023, the highest in history. Despite decades of global investment in clean energy, fossil fuels still provide over 80% of global energy use, a figure that has not changed for decades. In the absence of climate action, our world is on course to heat a blistering 3°C, perhaps more, potentially displacing one-third of humanity.

Studies forecast climate-related extinction of 14–32% of macroscopic species in the next ∼50 years, including 3–6 million animal and plant species. With continued warming, the frequency of wildfires will increase over 74% of the global landmass by the end of this century. Such assessments are conservative.

Of the 40 leading economies, all of which agreed in the 2015 Paris Climate Accord to take all necessary actions to stop global heating below 1.5°C, not one nation is on track to do what they promised. The energy plans of countries responsible for the largest GHG emissions would lead to 460% more coal production, 83% more natural gas, and 29% more oil in 2030 than is compatible with limiting global heating to 1.5°C, and 69% more fossil fuels than is compatible with the riskier 2°C target.

The market cost of oil, coal, and natural gas is distorted by subsidies and does not include negative externalities related to pollution, climate change, healthcare, and others. Worse, the false promise and widespread allure of unregulated quick fixes, such as “net-zero” contracts that lack monitoring, auditing, and verification. Investigations suggest that the great majority of products transacted on carbon offset markets remove very little GHG from the atmosphere, and models indicate that even direct removal of atmospheric CO2 does not recover former environmental conditions.

Imperialism, overpopulation, and resource extraction

Despite decades of international commitments to end deforestation, around 4.1 million hectares of primary tropical rainforest was lost globally in 2022—an increase of 10% over 2021—producing 2.7 Gt (giga or billions of tonnes) of CO2 emissions, equivalent to the annual fossil fuel emissions of India.

Global population growth amplifies the damage wrought by industrial capitalism. On 15 November 2022, the world’s population reached 8 billion people. Human population is expected to increase by nearly 2 billion in the next 30 years, and could peak at nearly 10.4 billion in the mid-2080s. With every additional person added to the planet, wild habitats are disturbed or destroyed by urbanism, agricultural activities, and resource consumption, with humanity demanding more than what the biosphere can sustainably provide.

Given the current state of the ecosphere, a 25% increase in population and projected doubling of economic activity by 2050 may drive major ecological regime shifts (i.e. forest to savannah, savannah to desert, thawing tundra, and others) well before 2080.

Human population growth, increased economic demands, rising heat, and extreme weather events put pressures on ecosystems and landscapes to supply food and maintain services such as clean water. Researchers warn that more than a fifth of ecosystems worldwide, including the Amazon rainforest, are at risk of a catastrophic breakdown within a human lifetime.

Global economics and values

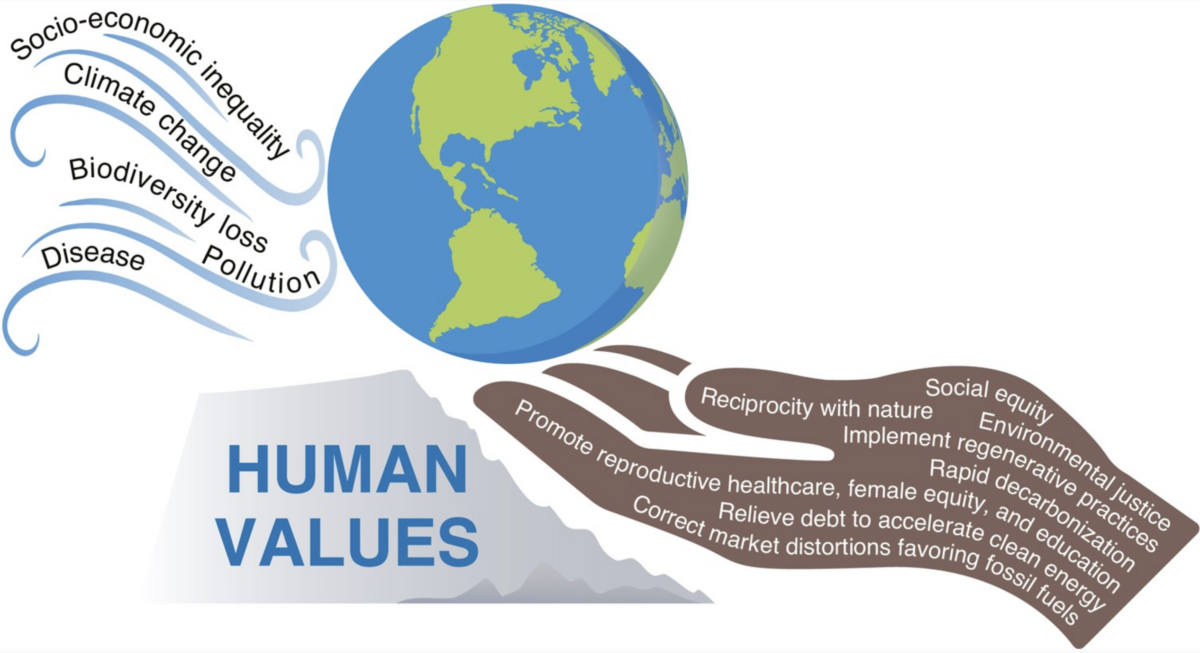

Convergence of worldwide trends threatens safe and sustainable human development: accelerating impacts from climate change, biodiversity loss caused by unsustainable consumption, extractive agriculture, natural resource exploitation and limitations, emergent disease, pervasive pollution, and socioeconomic injustice. To secure a safe future for humanity, global economics and values must protect the well-being of the natural world.

Climate realities and the road to action

In April 2023, CO2 levels measured at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawai‘i reached an annual peak of 424.8 ppm, more than 50% greater than the preindustrial level of 278 ppm. In the first decade of measurement at Mauna Loa (1959–1968), the average annual growth rate was 0.8 ppm per year. The average annual growth rate over the most recent decade (2014–2023) was 3 times that amount, 2.4 ppm per year, the fastest sustained rate of increase in 65 years of monitoring.

More than half of all industrial CO2 emissions have occurred since 1988 and 40% of the CO2 we emit today will still be in the atmosphere in 100 years, about 20% will still be there in about 1,000 years. The last time CO2 levels were this high was the Pliocene Climatic Optimum, 4.4 million years ago, when Earth’s climate was radically different; global temperature was 2–3°C hotter, beech trees grew near the South Pole, there was no Greenland ice sheet, no West Antarctic ice sheet, and global sea level was as much as 25 meters higher than today.

Atmospheric methane (CH4) growth has surged since 2020. Averaged over 2 decades, the global heating potential of CH4 is 80 times greater than CO2. The largest sources of atmospheric CH4 are wetlands, freshwater areas, agriculture, fossil fuel extraction, landfills, and fires. In 2023, atmospheric CH4 exceeded 1,919 ppb, on track to triple the preindustrial level of 700 ppb by 2030. Carbon isotopic signatures reveal microbial decomposition of organic matter as the major source of CH4 emissions, indicating that natural CH4-producing processes are being amplified by climate change itself. Is this a sign that global heating is shifting beyond our control?

Under an intermediate scenario (SSP2-4.5), GHG emissions are very likely to lead to heating of 1.6–2.5°C in the midterm (2041–2060), and 2.1–3.5°C in the long term (2081–2100). As of November 2023, 145 countries had announced or are considering net-zero targets, covering close to 90% of global emissions.

Even as the vast majority of countries pledged to slash their climate emissions, their own plans and projections put them on track to extract more than twice the level of fossil fuels by 2030 than would be consistent with limiting heating to 1.5°C, and nearly 70% more than would be consistent with 2°C of heating. The world has a 67% chance of limiting warming to 2.9°C if countries stick to the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) made under the 2015 Paris agreement. Emission cuts of 14 GtCO2 or 28% are needed by 2030 to keep within 2°C of warming. A reduction of more than 40% or 22 GtCO2 is needed for the 1.5°C threshold to be realistic.

Limiting warming to 1.5°C would require global emission reduction of 8.7% per year. Even with COVID-19 lockdowns limiting manufacturing, ground and air transportation, and other economic activities during 2020, emissions dropped by only 4.7%.

Under current national climate plans, emissions are expected to rise 9% above 2010 levels by the end of this decade even if NDCs are fully implemented. GHG emissions would fall to 2% below 2019 levels by 2030. Although these numbers suggest the world will see emissions peak this decade, that’s still far short of the 43% reduction against 2019 levels that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says is needed to stay within the 1.5°C target envisioned by the Paris Agreement.

Since the 26th Conference of Parties (COP) in 2021, nations have shaved just 1% off their projected emissions for 2030, and COP 28 in 2023 ended with no increase in ambition. Current pledges would lead to long-term global heating of 2.4–2.6°C, but on-the-ground policies put the world on track for heating approximately 3°C above preindustrial levels.

Climate indicators show that global heating reached 1.14°C averaged over the past decade, 1.26°C in 2022, and 1.45 ± 0.12°C over the 12-month period of 2023. Heating is increasing at an unprecedented rate of over 0.2°C per decade (perhaps faster) caused by a combination of annual GHG emissions at an all-time high of 54 ± 5.3 GtCO2e over the last decade, and reductions in the strength of aerosol cooling.

Climate outlook

Even the planned investment of $3.5B to develop four “direct air capture” hubs under the 2022 US Bipartisan Infrastructure Law will only remove the equivalent of 13 min of global emissions at full annual capacity. Planting 8 billion trees, one for every person on Earth, would remove the equivalent of only 43 hours of global emissions after the trees reached maturity decades from now, and the change in albedo related to the new ground cover increases the complexity of expected benefits.

The only honest strategy for today is radical, immediate cuts in fossil fuel use. Only after emissions have begun a rapid downward trajectory should investments in carbon removal (the engineering for which has yet to be defined or validated) occur with speed and at scale.

By 2050, over 300 million people living on coasts will be exposed to flooding from sea level rise. Climate change drives the spread of disease. Even if heating is held below 1.6°C, 8% of today’s farmland will be unfit to produce food. Declining food production and nutrient losses will result in severe stunting affecting 1 million children in Africa alone and cause 183 million additional people to go hungry by 2050.

Abrupt change

Earth’s biophysical systems are shifting toward instability, perhaps irreversibly. The IPCC has identified 15 Earth system components with potential for abrupt destabilizing change, including ice, ocean, and air circulation; large ecosystems; and precipitation. These systems are the pillars of life that permit stable plant, animal, and microbial communities, food production, clean water and establish the conditions for safe human development.

Oceans

Marine biodiversity is being decimated by more than 440,000 industrial fishing vessels around the world that are responsible for 72% of the world’s ocean catch. Over 35% of the world’s marine fishery stock is overfished and another 57% is sustainably fished at the maximum level. Marine heatwaves are increasing with negative impacts on marine organisms and ecosystems. Marine coastal biodiversity is at risk, with over 98% of coral reefs projected to experience bleaching-level thermal stress by 2050.

Relative to the period 1995–2014, global mean sea level is conservatively projected to rise 0.15–0.29 m by 2050, and 0.28–1.01 m by 2100 Higher rise would ensue from disintegration of Antarctic ice shelves and faster-than-projected ice melt from Greenland. On multiple occasions over the past 3 million years, when temperatures increased 1–2°C, global sea levels rose at least 6 meters above present levels.

Toxic metals such as mercury, lead, and cadmium accumulate in marine animals, causing health problems in fish species and human consumers. Plastics take hundreds of years to degrade, breaking down into microplastics that are ingested by fish, humans, and other organisms. Manufactured chemicals such as polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins are environmentally persistent toxins that accumulate in the tissues of marine animals, disrupting hormonal systems. Urban and agricultural runoff, and sewage contain pathogens, heavy metals, and organic compounds that harm marine animals and cause human health problems. Nitrogen pollution also results in toxic algal blooms and oxygen-depleted dead zones.

Terrestrial biome

Tropical forests now emit more carbon than they are able to absorb from the atmosphere. Forests are degraded by drought, pests, and wildfire related to climate change.

Only 2.9% of Earth’s land remains ecologically intact. Anthropogenic extinction rates are driving Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

Widespread terrestrial ecological decline has resulted from the combination of climate change, resource extraction, bushmeat hunting, and agricultural and urban development. Since 1970, vertebrate populations have declined 69%, and 1 in 4 species are at risk of extinction, in part because 75% of the terrestrial environment has been severely altered by human actions.

Agricultural development has further eroded ecosystem health, with over 15 billion trees per year lost since the emergence of agriculture; the global number of trees has fallen by over 45%. An estimated 67,340 km2 of global forest were lost in 2021 alone, unleashing 3.8 Gt of GHG emissions, roughly 10% of the global average. Such losses extend to wetland areas; more than 85% of the wetlands present in 1700 had been lost by 2000, and loss of wetlands is currently 3 times faster than forest loss.

Food and water security

Agriculture is responsible for 70% of global freshwater withdrawals. By one estimate, 94% of nonhuman mammal biomass is now livestock, and 71% of bird biomass is poultry livestock. 50% of all agricultural expansion has come at the expense of forests. In 2022, the rate of global deforestation was the equivalent of 11 soccer/football fields per minute, predominantly for cattle ranching and grain animal feed crops (such as soy) for export.

Today, agriculture uses half of all habitable land, and either through grazing or growing animal feed, 77% of that is dedicated to livestock. Animal agriculture is expanding. From 1998 to 2018 global meat consumption increased 58%. Cattle and the grain they eat use 1/3 of all available land surface, 1/3 of global grain production, and 16% of all available freshwater. Yet cattle agriculture only generates 18% of food calories and 27% of protein. Additionally, livestock feed demands a minimum of 80% of global soybean crop and over 50% of global corn crop. Thirty-five to 40% of yearly anthropogenic CH4 emissions are a result of domestic livestock production due to enteric fermentation and manure.

Under a range of GHG emission pathways, cropland exposure to drought and heat-wave events will increase by a factor of 10 in the midterm and a factor of 20–30 in the long term on all continents, especially Asia and Africa. Harvest failures across major crop-producing regions are a threat to global food security. Jet stream changes are projected to increase synchronous crop failure and lower crop yields in multiple agricultural regions around the world. For maize, risks of multiple breadbasket failures increase from 6– 40% at 1.5°C to 54% at 2°C. In relative terms, the highest climate risk increases, between 1.5 and 2°C heating, is for wheat (40%), followed by maize (35%) and soybean (23%).

Demand for wheat is projected to increase 60% by 2050. Harvests of staple cereal crops, such as rice and maize, could decrease by 20–40% as a function of heightened surface temperatures in tropical and subtropical regions by 2100.

Heat

The global land area affected by at least 1 month of extreme drought per year increased from 18% averaged over the decade 1951–1960 to 47% in the decade 2013–2022.

Even under moderate warming, heat and drought levels in Europe that were virtually impossible 20 years ago reach 1-in-10 likelihoods as early as the 2030s. Europe-wide 5-year megadroughts become plausible.

For thousands of years, fundamental limits on food and water security meant that human communities have concentrated under a narrow range of climate variables characterized by mean annual temperatures (MATs) around 13°C. With continued GHG emissions, global heating of 3°C is projected to drive a MAT >29°C across 19% of the planet’s land surface and displace one-third of the human population. Today, this MAT accounts for only 0.8% percent of Earth’s land surface, mostly concentrated in the deep Sahara.

In July 2023, for the first time in 20 years, the United States experienced locally acquired malaria infections. Six cases were confirmed in Florida and one in Texas, none related to international travel. In Seattle, cases of West Nile disease were reported for the first time.

Economic inequality, ecological destruction, and global security

The poorest half of the global population owns barely 2% of total global wealth, while the richest 10% owns 76% of all wealth. The poorest 50% of the global population contribute just 10% of emissions, while the richest 10% emit more than 50% total carbon emissions.

Climate purgatory

The IEA predicts a peak in fossil fuel demand by 2030, but reports show governments planning to increase coal, oil, and gas production well beyond climate commitments. This math does not align with the 1.5°C or even the 2°C warming targets. Many experts consider these targets nearly impossible due to the global reluctance to urgently phase out fossil fuels.

A new era of reciprocity with nature and among human societies

The purpose of this review is to draw immediate attention to the careless, foolish way that humanity is gambling with the future. Unless things change dramatically, and soon, damage to the natural world will have long-lasting consequences for species and ecosystems, and devastating upheavals for humanity.

Under current national plans, global GHG emissions are set to increase 9% by 2030, compared to 2010 levels. Yet the science is clear: emissions must fall by 45% by the end of this decade compared to 2010 levels to meet the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Yet renewable energy will not address the root problem of ecological overshoot, social justice, or pollution. Policies are needed that end the production of superfluous and luxury commodities, conserve energy at household and societal levels, stabilize global population, and replace the extractive model with one that emphasizes true sustainability so that more natural resources per capita become available and wealth is far more equitably distributed.

The shift away from an extractive, resource-driven global economy toward one that values human rights and livelihoods could redefine global economics and offer reasons for optimism. Halting global ecological decline and addressing the crises of climate change, biodiversity collapse, pollution, pandemics, and human injustice requires a shift in economic structures, human behavior, and above all, values.

To reverse the many negative impacts generated by our modern socioeconomic system there must be global investment in:

- Rapid and legitimate decarbonization, correcting market distortions favoring fossil fuels, avoiding the spurious trap of “net zero” as an excuse to continue polluting the atmosphere.

- Revising the basis for decision-making under the UNFCCC. Decision-making under the UNFCCC should be reorganized by transitioning from unanimous voting to qualified majority voting, enabling decisions to be made with agreement from a defined majority of member nations.

- Building a new era of reciprocity and kinship with nature, and decoupling economic activity from net resource depletion.

- Implementing sustainable/regenerative practices in all areas of natural resource economics including, especially, agriculture.

- Eliminating environmentally harmful subsidies and restricting trade that promotes pollution and unsustainable consumption.

- Promote gender justice by supporting women’s and girls’ education and rights, which reduces fertility rates and raises the standard of living.

- Accelerating human development in all SDG sectors, especially promoting reproductive healthcare, education, and equity for girls and women.

- In low- and middle-income nations, relieving debt, providing low-cost loans, financing loss and damage, funding clean-energy acceleration, arresting the dangerous loss of biodiversity, and restoring natural ecosystems.

A cultural shift in values

A new economic paradigm is needed to create a prosperous and harmonious future, meeting the challenges of a rapidly deteriorating world.

Earth is our lifeboat in the sea of space

“We are consuming and polluting the biophysical basis of our own existence.” Climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, disease, and social injustice risk the stability of human communities on Earth. We must stop treating these issues as isolated challenges, and establish a systemic response based on kinship with nature that recognizes Earth as our lifeboat in the cosmic sea of space.

There is no guarantee of a just, nourishing, and healthy future for humanity, and hope will not catalyze the change we need. That work must fall upon us, and it is clear from this review that we are past due for, and critically far away from, an appropriate reaction to the global emergency we have created.