CENTRAL JAVA: Rasjoyo could only watch in silence as his small wooden boat sailed through Semonet, a sleepy fishing village in the northern coast of Java he once called home.

Rice fields and farmlands were the first to be impacted as fresh water became more saline. Then the waves began pounding the row of houses, eroding the soft, sandy soil beneath them until these dwellings became one with the sea.

By the mid 2010s, residents began to trickle out of Semonet. Rasjoyo’s family were some of the last people to vacate their properties in 2022, having lived further inland.

By late last year, the village was completely deserted.

What happened to Semonet – located in the Central Java district of Wonokerto – is not unique.

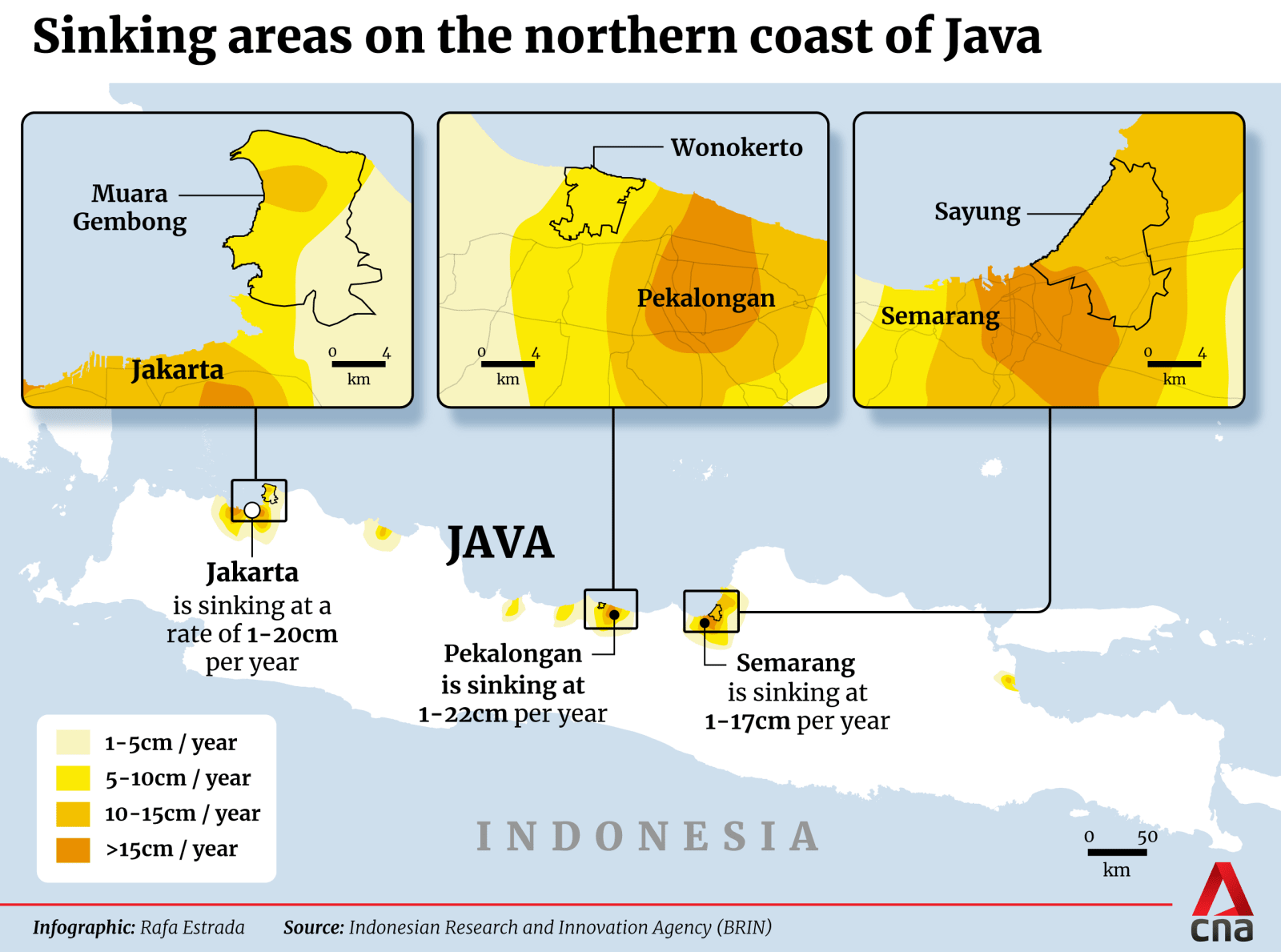

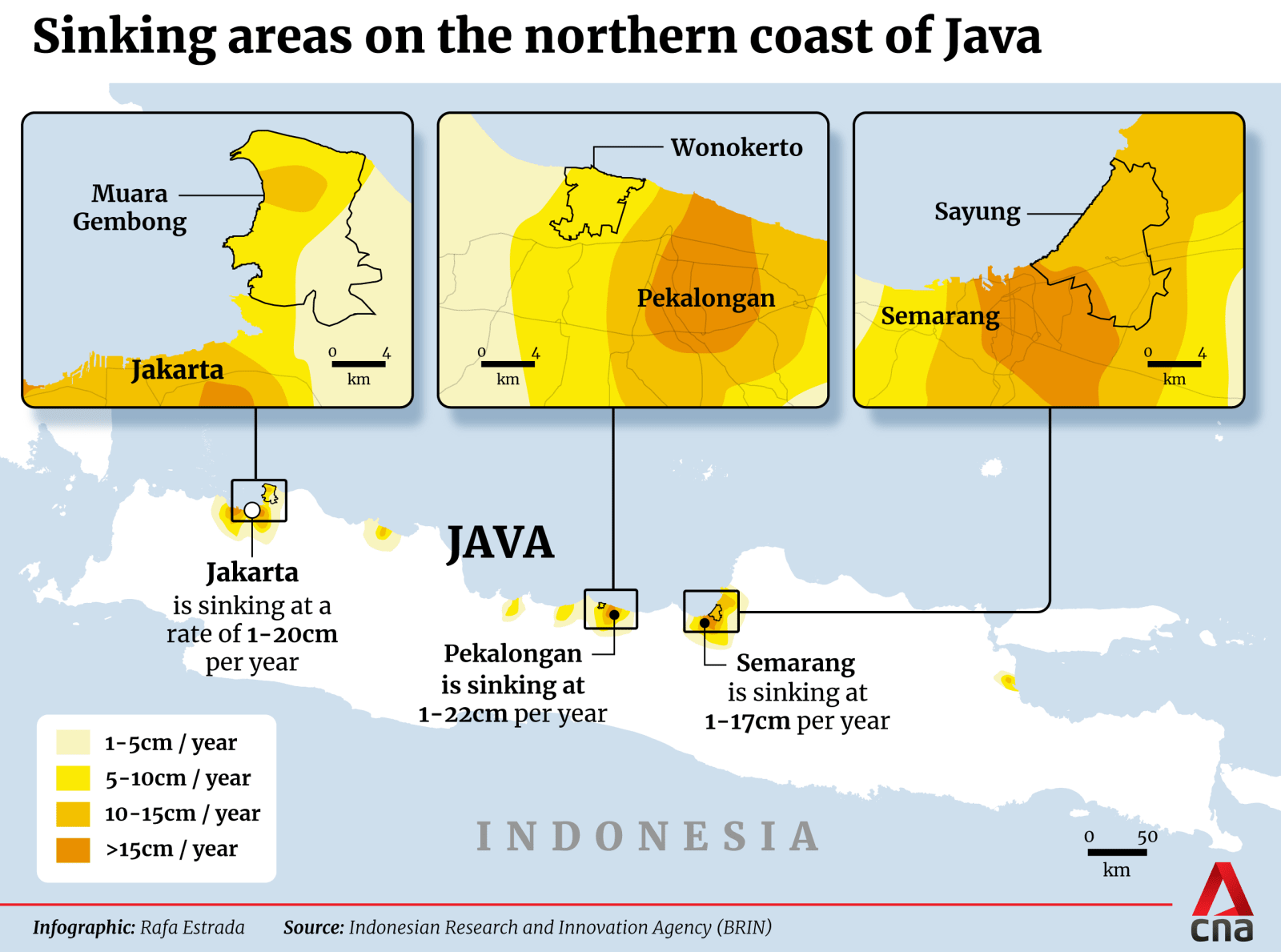

Along the northern coast of Java island, villages and urban communities are disappearing thanks to land subsidence, coastal abrasion and rising sea level.

In some areas, land has receded by more than 2km over the last 20 years, displacing thousands of people and causing millions of dollars in lost farmlands and residential areas.

Although these phenomena are also seen in the eastern coast of Sumatra and southern coast of Borneo, their spread and scale are nothing compared to what scientists are observing in Java, Indonesia’s most developed island where 56 per cent of the country’s 280 million population reside.

Unlike the hard, rocky soils of the south, the northern coast of Java sits largely on soft and unconsolidated sediments. Which is why cities like Jakarta, Pekalongan and Semarang, are sinking at a rate of between 1cm and 26cm every year.

The loose soils of these cities are compacted by the weight of man-made structures while the over-extraction of groundwater are causing ground level to recede as the earth beneath them deflates.

In February, the president announced that his administration will start building a giant sea wall which spans from Banten province in the western tip of Java to Gresik City in East Java. The two areas are 700km apart.

But with the Prabowo government rolling out a number of austerity measures which saw the Public Works Ministry’s budget dropping from 111 trillion rupiah (US$6.7billion) to 50 trillion rupiah this year, it is unclear how this massive project will be financed, despite the president insisting that “the money is ready”.

Even if Indonesia manages to find the money, experts say that it will take many years before the sea wall is ready. Meanwhile, for coastal communities on the brink of disappearing, time is running out.

About 7km east of Semonet, in the industrial city of Pekalongan, residents have to live in constant fear of rising sea level and tidal floods.

For decades, houses, businesses and farmlands relied on groundwater as nearby rivers have become polluted from the hundreds of batik factories and workshops dotting the city of 300,000 residents.

As a result, Pekalongan is sinking at a rate of up to 22cm a year with some estimates predicting that 90 per cent of the city will be below sea level by 2035.

With more than 40 per cent of its territory already below sea level, water had nowhere to go once Pekalongan got hit by heavy rainfall. The situation becomes worse when there is an occurrence of tidal surge or river overflow.

The same condition can be observed 80km east of Pekalongan in Central Java capital Semarang. The city of 1.7 million people is sinking at an average rate of 10cm per year with some areas already sitting 2m below sea level.

Flooding has become an annual fixture of Semarang, sometimes affecting more than 60 per cent of the city’s territory.

Central Java provincial secretary Sumarno, who also goes by one name, said billions of dollars have been earmarked and spent on building dikes, wave breakers and other infrastructures to save Pekalongan and Semarang from flooding.

Among them are a flood barrier to protect Pekalongan from sea surges and a 27km toll road spanning from Semarang to neighbouring Demak regency which will double as a tide gate.

The US$73 million Pekalongan barrier is scheduled to be operational this year while the US$918 million Semarang-Demak toll road is slated for completion in 2027.

These ongoing projects are the latest additions to various dikes, wave breakers and barriers meant to save Pekalongan and Semarang. Over time, these infrastructures – some of which are more than 20 years old – had become obsolete and needed to be reinforced and raised to keep up with the sinking land and rising sea levels.

The provincial secretary, however, said that there are areas like Semonet which are so devastated by sea intrusion the only viable option left is to relocate residents to safer areas.

Some 10km east of Semarang lies Rejosari village in Demak Regency. Two hundred families have abandoned their now sunken properties after the sea began encroaching their farmlands and homes in 2004. Over the next 20 years, saltwater has reached areas which are 4km away from where the coastline used to be.

Scientists estimated that at least 100 coastal areas along the northern coast of Java are on the verge of disappearing. This includes the country’s capital and biggest city, Jakarta, which experts predicted will have 95 per cent of its area sitting below sea level by 2050.

But experts are sceptical that building a 700km wall running almost the entire length of Java is the right solution to save these areas from sinking.

“Building a wall is a temporary solution,” said Mila, the urban planning expert.

Because the land is still sinking and sea level rising, such coastal barriers would still need to be raised and reinforced regularly.

The Indonesian government has been mulling the idea of creating a 30km long sea wall deep in the Java Sea for more than 10 years. However, rejection from local fishing communities and environmental activists forced the capital city government to put the plan on hold.

Indonesia’s Ministry of Public Works had previously estimated that it would cost 164 trillion rupiah (US$10 billion) to build the Jakarta sea wall.

To build a sea wall spanning almost the entire length of Java, as proposed by Prabowo, would require a budget many times larger, not to mention the various machinery needed to regulate water level as well as costs to operate and maintain it.

And building a wall does not address the elephant in the room: Over-extraction of groundwater which causes land to subside.