Europe’s most severe drought in decades is hitting homes, factories, farmers and freight across the continent, as experts warn drier winters and searing summers fuelled by global heating mean water shortages will become “the new normal”.

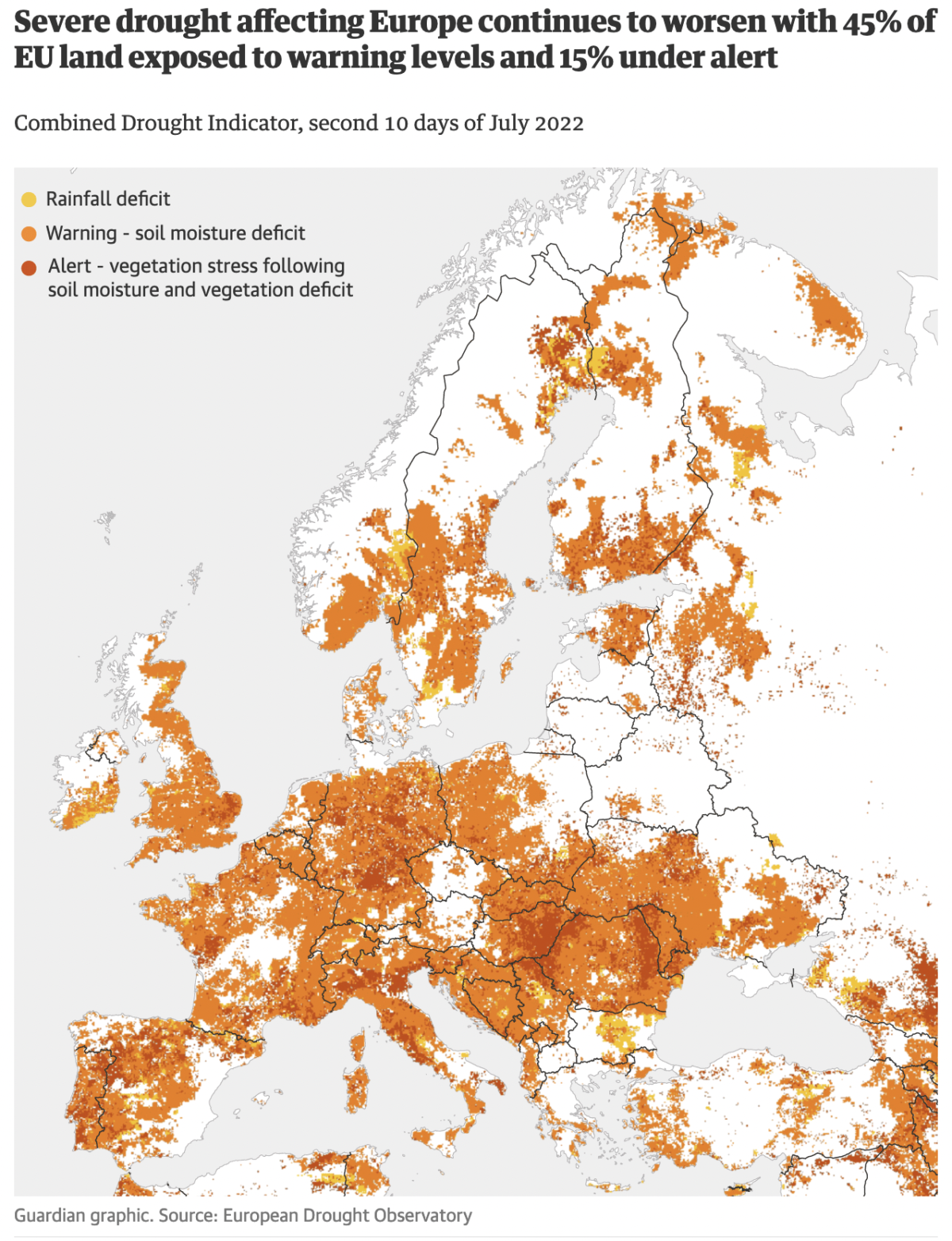

The EU European Drought Observatory has calculated that 45% of the bloc’s territory was under drought warning by mid-July, with 15% already on red alert, prompting the European Commission to warn of a “critical” situation in multiple regions.

Conditions have deteriorated since as repeated heatwaves roll across the continent.

France –

The prime minister, Élisabeth Borne, last week activated a crisis unit to tackle a drought Météo-France described as the country’s worst since records began in 1958.

More than 100 French municipalities have no running drinking water and are being supplied by truck, green transition minister Christophe Béchu said, adding: “We are going to have to get used to episodes of this type. Adaptation is no longer an option, it’s an obligation.”

With surface soil humidity the lowest ever recorded and July rainfall 85% lower than usual, water restrictions including hosepipe and irrigation bans are in place in 93 of the country’s 96 mainland départements, with 62 classified as “in crisis”.

Spain –

Spain’s water reserves are at all-time low of 40% and have been falling at a rate of 1.5% a week through a combination of increased consumption and evaporation, according to the government, in what is likely to be the driest of the past 60 years.

The country has received less than half its expected rainfall for the time of year for the past three months, with restrictions in place from Catalonia in the north-east to Galicia in the north-west as well as western Extremadura and Andalucía in the south.

Italy –

This year is also set to become the hottest and driest ever recorded in Italy. “I don’t know what we need to do anymore to make the climate crisis a political theme,” said Luca Mercalli, the president of the Italian Meteorological Society.

“No similar data in the last 230 years compares with the drought and heat we are experiencing this year. Then we have had storms … These episodes are growing in frequency and intensity, exactly as forecast by climate reports over the last 30 years. Why do we continue to wait to make this a priority?”

One of the most prominent manifestations of the crisis is the parched River Po. The flow rate of Italy’s longest waterway has fallen to one-tenth of the usual figure, while its water level is 2 metres below normal. The government declared a drought emergency in five northern regions, rationing drinking water, in early July. Villages around Lake Maggiore are being supplied by truck.

With no sustained rainfall in the region since November, risotto rice production in the Po valley, which accounts for about 40% of Italy’s agricultural output, is under threat. Growers have warned that up to 60% of the crop may be lost as paddy fields dry out and turn salty, with record low-water levels allowing more seawater into the delta.

Germany –

Water levels have also fallen to dangerous lows on the Rhine, a vital north-west European waterway used to transport oil, petrol, coal and other raw materials that connects Germany’s industrial heartland to the major ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp.

The river’s level on Monday was already lower than at the same point in 2018, when a severe drought eventually halted goods transport for 132 days. Some vessels are operating at 25% capacity to avoid running aground, driving up freight costs.

The drought has hit German waterways just as freight vessels are supposed to carry increased amounts of coal in order to service the power plants that the chancellor, Olaf Scholz, has reactivated in the face of Russia throttling deliveries of natural gas.

Belgium –

Forecasters reported the driest July since 1885. Despite a ban on farmers pumping water for crops, groundwater levels in Flanders are exceptionally low causing peatlands to dry out, raising concern about wildlife, including snipe.

Canals and rivers are also in bad shape: local authorities report many fish have died as the only water left in some waterways is industrial or sewage effluent.